A Broken Feedback Loop – ACTH’s Dysregulation

Nelson’s syndrome is a rare condition characterized by hyperpigmentation, excessive ACTH’s (adrenocorticotropic hormone) secretion, and adrenal tumor growth. It arises from a positive feedback loop between the pituitary gland and the adrenal glands, leading to the overproduction of ACTH and cortisol. Understanding the pathophysiology of ACTH dysregulation in Nelson’s syndrome is crucial for effective diagnosis and management.

Normal ACTH Secretion and the HPA Axis

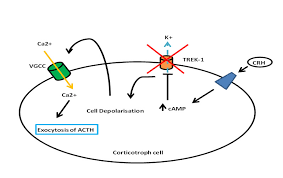

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is a complex neuroendocrine regulatory system that controls the body’s response to stress. The hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) in response to various stimuli, such as physical or emotional stress. CRH stimulates the pituitary gland to produce ACTH, which travels to the adrenal glands and stimulates the production of cortisol, a glucocorticoid hormone with wide-ranging metabolic and immunological effects.

A negative feedback loop normally regulates ACTH and cortisol levels. Cortisol binds to specific receptors in the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, suppressing the release of CRH and ACTH, respectively. This feedback loop ensures that cortisol levels are maintained within a narrow range necessary for normal physiological function.

A Broken Loop: ACTH Dysregulation in Nelson’s Syndrome

In Nelson’s syndrome, a pituitary tumor, typically an adrenocorticotropic carcinoma (ACTnoma), disrupts the normal HPA axis function. The tumor grows autonomously, producing excessive ACTH independent of CRH stimulation. This excess ACTH stimulates the adrenal glands to produce abnormally high levels of cortisol, leading to the characteristic clinical features of Nelson’s syndrome.

The positive feedback loop in Nelson’s syndrome is broken because the elevated cortisol levels cannot suppress ACTH production from the ACTnoma. This results in a vicious cycle of overproduction of ACTH and cortisol, further promoting tumor growth and worsening clinical symptoms.

Clinical Manifestations of Nelson’s Syndrome

The clinical manifestations of Nelson’s syndrome are primarily due to the chronic overexposure of the body to cortisol. These include:

- Cushingoid features: Facial roundness, truncal obesity, muscle wasting, skin fragility, and striae

- Hyperpigmentation: Darkening of the skin, particularly in sun-exposed areas

- Glucose intolerance and diabetes mellitus

- Hypertension

- Osteoporosis and fractures

- Psychiatric disturbances: Depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment

Diagnosis and Management of Nelson’s Syndrome

Diagnosing Nelson’s syndrome involves a combination of clinical evaluation, biochemical tests, and imaging studies. Biochemical tests typically reveal elevated ACTH and cortisol levels in the absence of suppression with dexamethasone, a synthetic glucocorticoid used to diagnose Cushing’s syndrome. Imaging studies, such as MRI, can help identify the pituitary tumor.

Treatment for Nelson’s syndrome aims to control excess ACTH and cortisol production, shrink the pituitary tumor, and prevent complications. Surgical resection of the tumor is the preferred treatment option, followed by radiation therapy in cases of incomplete resection or recurrence. Medical therapy with medications that suppress ACTH or cortisol production may be used before or after surgery or in patients who are not candidates for surgery.

Additional Notes

- The prevalence of Nelson’s syndrome is estimated to be around 1 in 25,000 to 50,000 individuals.

- The prognosis for Nelson’s syndrome depends on the extent of tumor resection and the presence of comorbidities.

- New therapeutic options, such as targeted therapies and immunotherapy, are being investigated for the treatment of ACTnomas.

The HPA Axis: A Delicate Dance of Hormones

Imagine a grand orchestral performance, where each instrument represents a vital hormone in the body’s symphony. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis plays a starring role in this intricate concert, conducting the body’s response to stress. Let’s break down the key players:

- The Conductor: The hypothalamus, located in the brain, acts as the maestro, releasing corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) in response to various physical or emotional stressors.

- The First Violin: CRH stimulates the pituitary gland, located just below the brain, to produce ACTH. Imagine ACTH as the first violinist, carrying the musical baton to the next section.

- The Brass Section: ACTH travels to the adrenal glands, situated atop the kidneys, and signals them to produce cortisol, the body’s main stress hormone. Cortisol, like the booming brass section, exerts wide-ranging effects on metabolism, immunity, and various bodily functions.

A Broken Melody: Dysregulation in Nelson’s Syndrome

In Nelson’s syndrome, the harmonious melody of the HPA axis turns into a discordant cacophony. The culprit? A rogue pituitary tumor, typically an adrenocorticotropic carcinoma (ACTnoma), throws the entire orchestra out of tune. This tumor acts like a broken instrument, churning out excessive ACTH independent of the conductor’s (hypothalamus’) cues.

HPA axis diagram with adrenal glands, pituitary gland, and hypothalamus labeled

The consequences are dire:

- Cortisol Overload: The extra ACTH fuels the adrenal glands, leading to overproduction of cortisol. Imagine the brass section blaring at full volume, drowning out all other instruments. This chronic cortisol excess wreaks havoc on the body, causing the characteristic Cushingoid features of Nelson’s syndrome, such as facial roundness, truncal obesity, and skin fragility.

- Positive Feedback Loop: Normally, high cortisol levels would act like a feedback signal, telling the hypothalamus to suppress CRH production and the pituitary gland to dial down ACTH. But in Nelson’s syndrome, the ACTnoma is a rogue element, unaffected by this feedback loop. The result? A vicious cycle of uncontrolled ACTH and cortisol production, amplifying the hormonal imbalance and fueling tumor growth.

Unmasking the Villain: Diagnosis and Management

Diagnosing Nelson’s syndrome requires a detective’s eye. Doctors gather clues from:

- Clinical evaluation: Identifying classic Cushingoid features and hyperpigmentation.

- Biochemical tests: Revealing elevated ACTH and cortisol levels, even after a dexamethasone suppression test (which normally suppresses cortisol production).

- Imaging studies: MRI scans to pinpoint the pituitary tumor.

Once the villain is identified, the battle begins. Treatment strategies aim to:

- Suppress ACTH and cortisol production: Medications like metyrapone or ketoconazole can help control hormone levels before or after surgery.

- Shrink the tumor: Surgical resection is the preferred option, followed by radiation therapy if necessary.

- Prevent complications: Managing comorbidities like diabetes and osteoporosis is crucial for long-term health.

Living with Nelson’s Syndrome: A Balancing Act

Living with Nelson’s syndrome presents ongoing challenges. Regular monitoring of hormone levels and managing potential complications are essential. However, with effective treatment and support, individuals can find ways to harmonize their internal orchestra, leading to a healthier and more fulfilling life.

Beyond the Basics: Exploring Further Avenues

While the existing treatment options offer relief, the fight against Nelson’s syndrome continues. Researchers are actively exploring new frontiers:

- Targeted therapies: Drugs designed to specifically attack the ACTnoma’s molecular pathways hold promise for more effective tumor control.

- Immunotherapy: Harnessing the body’s immune system to target the tumor is a promising avenue being investigated.

- Gene therapy: Correcting the genetic abnormalities within the tumor cells is a potential long-term solution.

Conclusion

Nelson’s syndrome is a challenging condition caused by a disruption in the HPA axis due to an ACTnoma. Understanding the pathophysiology of ACTH dysregulation in this condition is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective management. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment are essential to prevent the serious complications associated with chronic cortisol excess and improve the quality of life for patients with Nelson’s syndrome.

what are the effects and causes.

Vasopressin, also known as the antidiuretic hormone (ADH), plays a crucial role in the body’s regulation of water balance and.

Read MoreDopamine’s Impact on Corporate Culture and.

In the corporate world, the reward system is a pivotal tool for motivating employees and driving performance. However, when these.

Read More